The Weir Fishery: How a Weir is Built

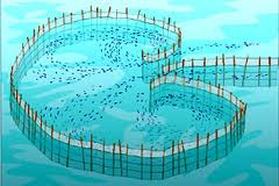

The weir fishery is an ancient and ingenious method for catching juvenile herring. You would probably know juvenile herring by the name, sardines. Technically a sardine is a juvenile herring that measures 4.5-7 inches in length. Indians of the Passamaquoddy Tribe used weirs made of brush many years ago. They built their weirs near the shore in shallow water. The weir is basically a large stationary trap that is situated to take advantage of the herring's natural movements. Herring swim in schools and are active during the night hours when it's dark. As the sun rises, herring begin to move to deeper water - they don't like light so as the sun comes up they head for deeper, darker water. Herring weirs are strategically situated to intercept them.

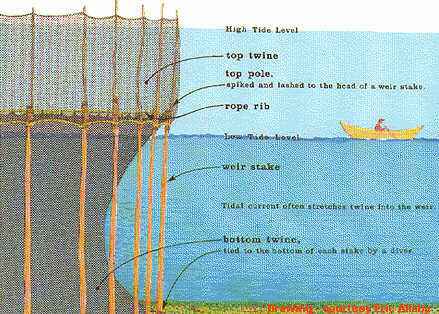

Today, the weir fishery is essentially the same although newer technologies enable us to build larger weirs and in deeper water. We still use brush but also stakes, poles, synthetic twine and piers. A weir has two levels - the bottom portion of the weir goes from the ocean floor to roughly the low water mark (remember that tides in the Bay of Fundy rise and fall about 22 feet in our area), and the top portion is from low water to high water.

Stakes - preferably hard wood because it lasts longer than soft wood - are driven in the ocean floor using a pile driver. An average size weir would have about 100 stakes, each one driven separately and about 6 feet (or a fathom) apart. In areas that the bottom is too rocky we would need to build a pier which is an L-shaped structure that has a platform that sits on bottom (piled high with rocks) and upright stakes on one side. So stakes form the bottom part of the weir and then poles are nailed in place to form the top portion, from high water to low water. Stakes and poles run up and down and are attached to ribbands that encircle the weir. Once the wood work is in place the next step is to prepare the twine.

There are two suits of twine for each weir - one for the bottom and one for the top. The bottom set of twine has to be tied down by a diver. The diver ties the twine to the base of each stake, all the way around the weir. Then the fishermen tie the top part of the bottom twine to the ribbands at the low water mark. The top twine is attached to the poles, top and bottom. Twine today is all synthetic. When I was younger, twine was made of cotton and had to be tarred each spring. That was quite a job! We'd boil the tar in barrels and dip the cotton twine into the barrel before spreading it on a huge roller to dry; we almost always got burned with the hot tar! The development of synthetic twine was a huge improvement. It's still a lot of work to repair the twine every spring but it's not nearly as messy as tarring cotton. Twine is put on the weirs in the spring and taken off in the fall. But it has to be repaired every year. That is, small and large holes and tears have to be mended. To do this we spread the twine out in large fields and work together - often for weeks - to get it ready for the weir.

Weirs very in size and depth. Many weirs would cover an acre and some are built in water 60' deep at low water - 90' in total.

Below are some good pictures that show how a typical weir works, what a pile driver looks like for a weir, what a sardine (herring) weir looks like from top to bottom, and the roller for tarring cotton twine that we used to use many years ago.

Today, the weir fishery is essentially the same although newer technologies enable us to build larger weirs and in deeper water. We still use brush but also stakes, poles, synthetic twine and piers. A weir has two levels - the bottom portion of the weir goes from the ocean floor to roughly the low water mark (remember that tides in the Bay of Fundy rise and fall about 22 feet in our area), and the top portion is from low water to high water.

Stakes - preferably hard wood because it lasts longer than soft wood - are driven in the ocean floor using a pile driver. An average size weir would have about 100 stakes, each one driven separately and about 6 feet (or a fathom) apart. In areas that the bottom is too rocky we would need to build a pier which is an L-shaped structure that has a platform that sits on bottom (piled high with rocks) and upright stakes on one side. So stakes form the bottom part of the weir and then poles are nailed in place to form the top portion, from high water to low water. Stakes and poles run up and down and are attached to ribbands that encircle the weir. Once the wood work is in place the next step is to prepare the twine.

There are two suits of twine for each weir - one for the bottom and one for the top. The bottom set of twine has to be tied down by a diver. The diver ties the twine to the base of each stake, all the way around the weir. Then the fishermen tie the top part of the bottom twine to the ribbands at the low water mark. The top twine is attached to the poles, top and bottom. Twine today is all synthetic. When I was younger, twine was made of cotton and had to be tarred each spring. That was quite a job! We'd boil the tar in barrels and dip the cotton twine into the barrel before spreading it on a huge roller to dry; we almost always got burned with the hot tar! The development of synthetic twine was a huge improvement. It's still a lot of work to repair the twine every spring but it's not nearly as messy as tarring cotton. Twine is put on the weirs in the spring and taken off in the fall. But it has to be repaired every year. That is, small and large holes and tears have to be mended. To do this we spread the twine out in large fields and work together - often for weeks - to get it ready for the weir.

Weirs very in size and depth. Many weirs would cover an acre and some are built in water 60' deep at low water - 90' in total.

Below are some good pictures that show how a typical weir works, what a pile driver looks like for a weir, what a sardine (herring) weir looks like from top to bottom, and the roller for tarring cotton twine that we used to use many years ago.

The Weir Fishery: How Fish are Harvested

My two grandsons and I hauling in the seine!

Much of the technology and tools used to seine a weir have remained relatively the same over the years. However, a lot of things have changed as well. In order to keep things simple, I'm going to talk about how we seine the weir now.

The first step is tending the weir for fish. This means constantly checking the weir and getting into a routine where sleep doesn't exactly happen during the nighttime (unless it's blowing or you manage to sleep while someone else rows). So, when you tend a weir, you go out during the middle of the night according to the tide and the moon. The best time to go out is during a quarter-moon or when the moon is covered with dense fog or clouds. Different weirs are better during different times of tide. Knowing what tide works for which weir is learned through experience.

When tending weir, you power to the weir in an outboard and then shut the motor off and row. Herring are very sensitive to the smallest sound. While rowing you must listen for the fish (a sound like rain on the water) and be extremely quiet. The least bit of noise risks scaring the fish away. Even shifting your body weight in the skiff can spook them and ruin the catch. Rowing quietly (feathering the oars so there is no sound of water dripping off the oar) is crucial. This is a skill that takes lots of practice to learn and some people never completely master it no matter how hard they try. So we look for fish during the night but we often don't know if we've caught any until the next morning. We'll go back out and drift down through the inside of the weir.

Once inside the weir we look at the fathometer to see if there are fish. If there are fish, we can judge how many herring there are by the density on the screen. You always have to estimate publicly, to the buyer, lower than what you actually think is there; it is never good to fall short. The buyer usually knows how much different people under-judge and takes that into consideration. He tells me I usually am under about 1/3 of the catch. So I might say that we have 30 hogsheads. That's the unit for measuring fish and it's a little more than half a ton. The buyer might think that we might have as many as 40 hogsheads if I say we have 30. But I'd rather underestimate than overestimate.

If there are fish, we shut up the mouth of the weir to trap the herring in the weir and wait we have market. We might get some sleep during the night or a cat nap during the day but once we have fish, sleep doesn't matter if you have a chance to get market. When herring are plentiful, you might wait days to get market, but if fish are scarce, you can usually get a boat the same day you catch them. Some weirs have a holding pound where you can keep fish you've already caught and open the main weir up to try to catch more. Our best weir, though, doesn't have a pound because of the location. So we always hope to sell fish as fast as we catch them.

To seine the weir, you plan a time (usually on the low-water slack tide) when the buyer can send a sardine carrier to the weir and be there at the time when you seine. Meanwhile, we are getting the purse-seine (nets) into the boat, all of the back-lines and crew together. Usually 2-3 skiffs go out, and most times a boat-full of onlookers in the lobster boat (it is quite an awesome scene to watch). Might as well also say that we made the center fold of Canadian Geographic one month. Once we get out to the weir, there is finally a time to rest as we sit and wait for the tide to slack. This is when the best yarns happen! It is not unusual for some arguments to also take place as crew tries to judge when the tide is slacking. This is my job but my family doesn't hesitate to argue. You know the tide is slacking when I can hold the oar in the water - straight down - and there is no pressure. My son throws rockweed in the water to test the current.

When the tide slacks, the crew plumbs the seine against the weir (lets the seine out tightly against the weir) and circles the weir with the seine, banging the oars and thumping your feet to scare the fish into the right spot. I am old now so I tend the backline at the mouth of the weir to keep the seine in the right shape. A lot of the time I have guests to keep me company. My wife comes with me or my granddaughter, and they help me listen. I'm deaf, so I don't hear all the orders they give me as well as they want me to, but I do my job and they'll miss me someday.

Around the leaded bottom of the seine is the purse-line. It's a set of rings that has a rope through it. Once we have the fish trapped into the middle of the seine and the ends are back together, we then can pull the purse-line in and haul the bottom of the seine to us and into a skiff. Boy, that little wench has made some difference for my back and knees when pulling in the purse-line and the purse-rock. We pull our guts out and get our hands full of sea-urchins (which we call whore's eggs). And then the real work starts...

Our job is to get the fish tight enough in the seine so they are dried up (at the surface of the water with no room to move). It's important to have them tight, but not so tight that they smother. We keep circling the seine and pulling it into the skiffs. Boy that is heavy. Sometimes there are 50-75 tons of fish in that seine, and other times 5; the harder it pulls the better. Once the seine is pulled in, the sardine carrier lowers a 6-inch diameter flexible hose into the seine - it's like a vacuum and the sardine carrier uses it to pump the fish into the the sardine carrier's hold. A hold can hold 50-60 tonnes of fish. We measure in hogsheads. One hogsead is 1200 pound of fish. I've seen there be hundreds of hogsheads pumped out of a weir; so many that we have to call another carrier or dump 'em back into the weir for another day.

Once the carrier has left with our catch of the day, we have to haul the seine, haul the backlines in, and get ready for another nights fishing. Many times I've gone days without more than a nap because we tend at night and hopefully seine during the day.

And this explanation was if everything goes right. Many times we have to seine more then once or twice to get the herring. We also can misjudge the slack tide and miss it and have to wait for another slack tide. We sometimes catch things we don't want to catch in the weir or seine; it's not uncommon to catch a tuna fish, whale, shark, porpoise, or other species. Dogfish are just about the worst; I've seen times where we would fill 3 skiff-loads full of the darn things. All fish bigger than herring need to be removed from the seine before we can actually pump - if we don't get them out and they go through the pump they can cut the fish and make a mess.

Also, there are times we go through all of that and not have a single fish or not be able to sell them. The weir fishery is a gamble and you never know if the fish are going to come or not. Some years are good and others are bad. If not this year, then maybe next year. I have 4 weirs and it costs about $3000 to repair one weir, plus months of work. But, that's fishing and I like it all!

A hogshead goes for about $140 this year; I remember when it was $4. You can go all summer and not catch a single fish, and then make a summer's work in a night or two. In 1951, I made enough money in the month of September to build my house ($10,000). I just hope that the fishery remains good for my family and future generations to come.

The first step is tending the weir for fish. This means constantly checking the weir and getting into a routine where sleep doesn't exactly happen during the nighttime (unless it's blowing or you manage to sleep while someone else rows). So, when you tend a weir, you go out during the middle of the night according to the tide and the moon. The best time to go out is during a quarter-moon or when the moon is covered with dense fog or clouds. Different weirs are better during different times of tide. Knowing what tide works for which weir is learned through experience.

When tending weir, you power to the weir in an outboard and then shut the motor off and row. Herring are very sensitive to the smallest sound. While rowing you must listen for the fish (a sound like rain on the water) and be extremely quiet. The least bit of noise risks scaring the fish away. Even shifting your body weight in the skiff can spook them and ruin the catch. Rowing quietly (feathering the oars so there is no sound of water dripping off the oar) is crucial. This is a skill that takes lots of practice to learn and some people never completely master it no matter how hard they try. So we look for fish during the night but we often don't know if we've caught any until the next morning. We'll go back out and drift down through the inside of the weir.

Once inside the weir we look at the fathometer to see if there are fish. If there are fish, we can judge how many herring there are by the density on the screen. You always have to estimate publicly, to the buyer, lower than what you actually think is there; it is never good to fall short. The buyer usually knows how much different people under-judge and takes that into consideration. He tells me I usually am under about 1/3 of the catch. So I might say that we have 30 hogsheads. That's the unit for measuring fish and it's a little more than half a ton. The buyer might think that we might have as many as 40 hogsheads if I say we have 30. But I'd rather underestimate than overestimate.

If there are fish, we shut up the mouth of the weir to trap the herring in the weir and wait we have market. We might get some sleep during the night or a cat nap during the day but once we have fish, sleep doesn't matter if you have a chance to get market. When herring are plentiful, you might wait days to get market, but if fish are scarce, you can usually get a boat the same day you catch them. Some weirs have a holding pound where you can keep fish you've already caught and open the main weir up to try to catch more. Our best weir, though, doesn't have a pound because of the location. So we always hope to sell fish as fast as we catch them.

To seine the weir, you plan a time (usually on the low-water slack tide) when the buyer can send a sardine carrier to the weir and be there at the time when you seine. Meanwhile, we are getting the purse-seine (nets) into the boat, all of the back-lines and crew together. Usually 2-3 skiffs go out, and most times a boat-full of onlookers in the lobster boat (it is quite an awesome scene to watch). Might as well also say that we made the center fold of Canadian Geographic one month. Once we get out to the weir, there is finally a time to rest as we sit and wait for the tide to slack. This is when the best yarns happen! It is not unusual for some arguments to also take place as crew tries to judge when the tide is slacking. This is my job but my family doesn't hesitate to argue. You know the tide is slacking when I can hold the oar in the water - straight down - and there is no pressure. My son throws rockweed in the water to test the current.

When the tide slacks, the crew plumbs the seine against the weir (lets the seine out tightly against the weir) and circles the weir with the seine, banging the oars and thumping your feet to scare the fish into the right spot. I am old now so I tend the backline at the mouth of the weir to keep the seine in the right shape. A lot of the time I have guests to keep me company. My wife comes with me or my granddaughter, and they help me listen. I'm deaf, so I don't hear all the orders they give me as well as they want me to, but I do my job and they'll miss me someday.

Around the leaded bottom of the seine is the purse-line. It's a set of rings that has a rope through it. Once we have the fish trapped into the middle of the seine and the ends are back together, we then can pull the purse-line in and haul the bottom of the seine to us and into a skiff. Boy, that little wench has made some difference for my back and knees when pulling in the purse-line and the purse-rock. We pull our guts out and get our hands full of sea-urchins (which we call whore's eggs). And then the real work starts...

Our job is to get the fish tight enough in the seine so they are dried up (at the surface of the water with no room to move). It's important to have them tight, but not so tight that they smother. We keep circling the seine and pulling it into the skiffs. Boy that is heavy. Sometimes there are 50-75 tons of fish in that seine, and other times 5; the harder it pulls the better. Once the seine is pulled in, the sardine carrier lowers a 6-inch diameter flexible hose into the seine - it's like a vacuum and the sardine carrier uses it to pump the fish into the the sardine carrier's hold. A hold can hold 50-60 tonnes of fish. We measure in hogsheads. One hogsead is 1200 pound of fish. I've seen there be hundreds of hogsheads pumped out of a weir; so many that we have to call another carrier or dump 'em back into the weir for another day.

Once the carrier has left with our catch of the day, we have to haul the seine, haul the backlines in, and get ready for another nights fishing. Many times I've gone days without more than a nap because we tend at night and hopefully seine during the day.

And this explanation was if everything goes right. Many times we have to seine more then once or twice to get the herring. We also can misjudge the slack tide and miss it and have to wait for another slack tide. We sometimes catch things we don't want to catch in the weir or seine; it's not uncommon to catch a tuna fish, whale, shark, porpoise, or other species. Dogfish are just about the worst; I've seen times where we would fill 3 skiff-loads full of the darn things. All fish bigger than herring need to be removed from the seine before we can actually pump - if we don't get them out and they go through the pump they can cut the fish and make a mess.

Also, there are times we go through all of that and not have a single fish or not be able to sell them. The weir fishery is a gamble and you never know if the fish are going to come or not. Some years are good and others are bad. If not this year, then maybe next year. I have 4 weirs and it costs about $3000 to repair one weir, plus months of work. But, that's fishing and I like it all!

A hogshead goes for about $140 this year; I remember when it was $4. You can go all summer and not catch a single fish, and then make a summer's work in a night or two. In 1951, I made enough money in the month of September to build my house ($10,000). I just hope that the fishery remains good for my family and future generations to come.